Albert Nerken School of Engineering: Senior Snapshots 2015

POSTED ON: May 20, 2015

For the third and final part in our 2015 series of "Senior Snapshots" focusing on each of the three schools at The Cooper Union [see parts one and two], we turn to four soon-to-be graduates of the Albert Nerken School of Engineering. Osaze Udeagbala, Jackie Song, David Katz and Quinee Quintana will each graduate with a different disciplinary focus, but all report the same experience of being profoundly affected by the school's culture of community support. We talked with them about where they came from, what they worked on in their final year, and where they are headed next.

Osaze Udeagbala, who is poised to graduate from the Bachelor of Science in Engineering program, will be a doctor one day. That seems certain. Just hearing how passionately he talks about his bio-chemical work would convince anyone of his dedication. It also seems certain that the world will be a little better for having Osaze working as a doctor. He speaks just as passionately about how he hopes to help find solutions for diseases that have long plagued West Africa.

Osaze Udeagbala, who is poised to graduate from the Bachelor of Science in Engineering program, will be a doctor one day. That seems certain. Just hearing how passionately he talks about his bio-chemical work would convince anyone of his dedication. It also seems certain that the world will be a little better for having Osaze working as a doctor. He speaks just as passionately about how he hopes to help find solutions for diseases that have long plagued West Africa.

"From the get-go I was interested in medicine — it was far from unfamiliar,” says Osaze, who was born and raised in Columbus, Ohio to Nigerian immigrant parents. “I was exposed early. My mother is a doctor in primary care. One reason engineering school excited me is that there is this huge practical impact that you can have on people's lives. You design a building, a material, a device, and you have the technical know-how to understand and communicate the impact of that work in the world. But then you implement it, and something unexpected happens. The thing is, you still need to solve the problem. This is the same exact thing that I find exciting about the world of medicine."

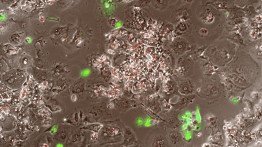

To that end he has spent part of his senior year in a laboratory at Weill Cornell Medical College working on a liver tissue-engineering project. "The idea is to explore the relationship between different cell types of the liver in order to create a better micro-scale model of the liver. This is useful for several purposes including disease modeling and drug development. For example, we could be better at screening out liver-toxic drugs before clinical trials.”

This fall Osaze will begin studying at NYU School of Medicine. He hopes to focus his energies eventually on West Africa, where he has visited on a number of occasions. “My long-term goal is to find a way to bring together the opportunities in the pharmaceutical industry and the needs in the realm of tropical infectious disease,” Osaze says. “Considering where I am right now, it’s hard to say how my plans will change. I do look forward, though, to being able to appreciate the nuances of medicine. I have a feeling my academic journey will impact my trajectory in ways I cannot yet fully appreciate.”

Osaze also has been active outside of his interest in bio-engineering. He spent two years on the Student Council and revived a dormant Black Student Union during his time at school. "Something I have learned while at Cooper is how people who have fundamentally different ways of viewing the world can have a conversation. By virtue of being at Cooper Union at this particular time in its history, I learned plenty about politically sensitive discourse."

He reflects on his undergraduate experience: “I’m really grateful to have spent four years here. I met people here that I know I never would have had the chance to meet had I not entered this place. Some of the professors I’ve had I will be forever grateful to. The Cooper environment really lends itself to a close relationship between the students and the faculty. With one in particular, I took more than a half-dozen classes. I don’t know where else that happens.”

Growing up in Edison, New Jersey, Jackie Song, who will graduate with a degree in mechanical engineering, was a fan of "How It’s Made," the television series that shows how products are manufactured. Always a tinkerer, Jackie was intrigued by the factories featured on the show. “They had great shots of huge machines. I think it was mostly the visual aspects of these machines that really drew me in.” Always interested in art, she thinks that the visual aspects of mechanical engineering appealed to her: “It seemed to be the most visually interesting. The projects I’m most interested in are the ones that move.”

Growing up in Edison, New Jersey, Jackie Song, who will graduate with a degree in mechanical engineering, was a fan of "How It’s Made," the television series that shows how products are manufactured. Always a tinkerer, Jackie was intrigued by the factories featured on the show. “They had great shots of huge machines. I think it was mostly the visual aspects of these machines that really drew me in.” Always interested in art, she thinks that the visual aspects of mechanical engineering appealed to her: “It seemed to be the most visually interesting. The projects I’m most interested in are the ones that move.”

She hadn’t known about The Cooper Union until she started researching colleges, and it seemed like a good fit. Her expectations, she says, were met and exceeded: she found that her professors at The Cooper Union and the encouraging environment of the school made her confident about her ability to thrive as an engineer. “All of the many hands-on engineering projects I've done here have been incredibly valuable to me. Vastly open-ended by design, each one was a chance to take creative risks and explore interests just outside the core framework of the curriculum,” she says.

For her senior project, Jackie teamed with fellow mechanical engineering senior Peter Ascoli to develop a 3D printer that can produces objects capable of bearing much heavier loads than those made by conventional 3D printers. While most printers are designed to use a flat-layer method of printing, Jackie and Peter deployed a curved-layer 3D printing method, which creates far stronger models. To that end, the pair created what Jackie calls “a promising carbon fiber reinforced polymer filament”—a filament being a strand of heat-responsive plastic which a 3D printer uses to build a form. They then converted a robot arm into a 3D printer to give them greater flexibility in positioning the release of those carbon fibers. “This positioning flexibility is especially important for taking full advantage of the strength of the carbon fiber composite filament,” Jackie says. She believes that her work with Peter provides a foundation for future researchers to expand on.

Besides her studies, Jackie plays flute with Poco a Poco, a classical music group at Cooper, joining in her sophomore year when the group began. She also performs with the Brooklyn Wind Symphony.

After graduation, Jackie, ever fascinated by machinery, will be an engineering intern at Blue River Technology in Sunnyvale, CA, a hub in Silicon Valley. She will be working on automated farming technology. “I’m really looking forward to it. I’ll be working on what some people call 'farm robots.' They detect and analyze plants in the field. There’ll be mechanical and some electrical aspects too it.”

As a young woman entering the profession, Jackie is aware of the gender gap in engineering, particularly in the mechanical discipline. “I think that starts early in childhood. I would get the dolls and my brother would get the building toys,” she says. She credits her time at The Cooper Union with helping her figure out where her passions lie. “When we come into Cooper, we have no idea what engineering really is. It’s a little scary, but I’m so glad I stuck with it. I have a much better idea of what I like to do and what I’m excited by.”

Even before the first semester of his senior year was complete, David Katz knew he would be working for Google at their Manhattan offices starting this June. “I’ll be working on the knowledge graph component of the search feature,“ he says, referring to the list of information on the upper right side of the screen that appears after many Google searches. “It’s an algorithm that tries to give you what you’re looking for without having to click a link.”

Even before the first semester of his senior year was complete, David Katz knew he would be working for Google at their Manhattan offices starting this June. “I’ll be working on the knowledge graph component of the search feature,“ he says, referring to the list of information on the upper right side of the screen that appears after many Google searches. “It’s an algorithm that tries to give you what you’re looking for without having to click a link.”

Although he had a job lined up so early, David hardly coasted through the year. Instead, he will simultaneously receive a bachelor of science and a master's degree in electrical engineering. The senior wrote his master's thesis while working on his final undergraduate project. A native of Stamford, CT, David says he had known about Cooper all his life and had always wanted to attend. “After taking a tour during my senior year of high school and interacting with current students, I knew it was a great fit for me both because of the technical rigor and tight-knit culture.”

He was always drawn to math, science and technology, and in the eighth grade he worked on a year-long research project related to chess computers. “While the problem of beating humans at chess with computers was already solved, I was inspired to be part of solving the next wave of interesting technical challenges.”

For his senior project, David, who is president of the school’s chapter of the Association for Computing Machinery, teamed up with fellow electrical engineering seniors Chris Curro and Mark Bryk to design an app to transcribe conversations in real time. The three realized that they all shared an interest in audio processing, especially multi-microphone setups. This would allow the software to capture roving conversations, as at a cocktail party. But it would also require an expensive microphone array. Instead, they focused on a more controlled environment with a clear need for real-time transcriptions: the conference room. All that participants would require is a smart phone, making the app considerably more practical.

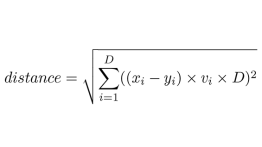

The task requires software that can accurately recognize voices of the different participants—the more people, the more difficult the problem: “The source separation—filtering the audio into distinct vocal tracks—is a really challenging algorithm.” Before a meeting begins, phones are placed on a table and calibrated to each other. “The calibration procedure lets us figure out where the phones are on the table in relation to each other and the precise time they started recording,” he says.

At the same time, David wrote his master’s thesis about a proposed solution to a critical problem in software engineering: how can you efficiently use computing to analyze a set of similar entities such as matching recommendations to user preferences? For instance, he says, this kind of software is at play when your Netflix account suggests other movies based on your our inferred preferences, or when Google search provides you with the most relevant results to a query. His work focused on modifying conventional algorithms to allow users to weigh the importance of specific features, providing them with more control over the results.

Never one to rest, this month David, along with fellow EE senior Caleb Zulawski and EE junior Harrison Zhao, competed in Dream It. Code It. Win It., a student software competition. Their project won the Ingenuity Award, which comes with a $5,000 prize. Their entry, "String to String," which digitally encodes writing on a blackboard, was first created at HackCooper, a hackathon that gives participants 24 hours to conceive, design and prototype a hardware or software project. “We used strings, pulleys, weights, ultrasonic distance sensing, a radio transmitter, geometry, and some filtering algorithms to develop an efficient method for encoding a blackboard at a high resolution for less than 40 dollars,” David says.

Looking back at his time in the labs during his four years, David recalls the hard work but also having a great deal of fun ambushing friends with nerf guns and squirt rings. At one point flying model helicopters around the labs got to be so prevalent, he says, that a specific rule had to be made against it. “All of the time spent staying up late, wondering why my circuits keep overheating, why my programs keep crashing or what the heck a Fourier transform does was so worth it.”

Quinee Quintana, who will graduate this year with a degree in civil engineering, has had many unexpected, transformative experiences during her four years at The Cooper Union. She discovered abilities she didn't know she had and she accomplished things she didn't know she could accomplish. The first was just getting in the door.

Quinee Quintana, who will graduate this year with a degree in civil engineering, has had many unexpected, transformative experiences during her four years at The Cooper Union. She discovered abilities she didn't know she had and she accomplished things she didn't know she could accomplish. The first was just getting in the door.

Quinee grew up on Staten Island, where trips to construction sites with her carpenter father inspired an interest in buildings. In school she had an aptitude for math and science that, along with a tip from a family friend about The Cooper Union, inspired her to apply. She did so in spite of a guidance councilor's active discouragement, suggesting it was too much of a reach. Her nothing-to-lose application would be the first in a series of carpe diem choices with great outcomes. "Some miracles happen!" Quinee says.

Her next accomplishment was meeting The Cooper Union's famously rigorous expectations of its students. "The Cooper Union changed me academically," she says. "Most people come here thinking, 'High school was a breeze.' And then Cooper beats you down and everyone is on the same playing field. At first it was really tough. There were times where I thought, 'I don't have what it takes to be an engineer. This is crazy.' I struggled in a lot of my classes, but there were fellow classmen as well as upperclassmen who reached out to help. I was worried that I would have to fight for my own good grades. But everyone is always encouraging and helping out."

Quinee's work has culminated in two major group projects during her senior year. The first, required of all graduating civil engineering students, was to replicate the process of developing a parcel of land in New York City. Quinee's team chose a space near the United Nations to propose building a recreational center with a park attached. "The project was a bit of a struggle," she says. "It's not your typical construction job. It has a lot of gyms. What we learned in our classes is that you typically have a concrete deck with beams and columns to support the building. But with a gym you don't want columns. It's easy if you have a one-story gym but it is uncommon to do multiple stories of gym space on top of each other. So that took a lot of extra research and design."

Quinee's other project this past year proved to be the most physically exhausting of her time here, she says. Along with a team of Cooper students she helped design, cut and weld the components of a 19-foot bridge as part of the annual Student Steel Bridge Competition. The exhausting part was building it, many times over, as the team practiced constructing it in as little time as possible while being mindful of a complex set of rules and restrictions. Civil engineering students from the New York-metro area competed in May. The Cooper team came in third with an impressive time of under 25 minutes.

But it was in non-academic ways that Quinee surprised herself most. "What really changed me was my involvement in extracurricular groups, like singing with the Coopertones, the a capella group. I was never the performing type in high school. I also joined The Cooper Union Intervarsity Christian Fellowship. The Cooper Intervarsity in general has been the shining example of how the Cooper community works. It is close knit and people look out for each other."

After graduating Quinee will move on to a full-time position at Ysreal A. Seinuk, P.C., where she interned as a student. It is the perfect spot for her, she says, since it focuses on structural engineering—her favorite form—and has a cadre of Cooper graduates. "It gives me the close-knit community sense that I had at Cooper," she says.