Thesis Year Snapshots: 2015

POSTED ON: May 18, 2015

In this first of three articles featuring 2015 graduates of The Cooper Union [see parts two and three], we focus on three fifth-year students from The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture. Their thesis work all shares an interest in the reclamation of memory in built form. Arta Perezic, Dustin Atlas and J.A. Alonzo searched landscapes, buildings, drawings and texts for sources that could give up secrets about the rich history of their thesis sites. Arta used photography to develop a set of pictographs to discover the cultural influences on a city in Montenegro. J.A. used Manila’s remaining tributaries known as esteros as the point of entry for understanding an unfinished plan for that city. Dustin imagined how a common element of city buildings—the fire escape—could be used to radically alter the function of a theater. We talked to each of them about their thesis proposals and their plans for the future.

After traveling to southern Montenegro last summer to visit Ulqin, her parents’ home town, Arta Perezic chose to study its oldest section to unearth its history. Though it is approximately 2,000 years old, it has only a vague record of the various cultures that once occupied it, according to Arta. These include the Illyrians, Byzantines, Venetians and Ottomans. Today, the city is the center of Albanian Montenegro. Arta decided to look at Ulqin’s long and varied history through its built environment to understand her own relationship to the multi-layered city. Along the way she rethought approaches to research and preservation. “I’m taking this opportunity to develop a new methodology for preserving a city,” she says. Her proposal is entitled “The Forever City.”

After traveling to southern Montenegro last summer to visit Ulqin, her parents’ home town, Arta Perezic chose to study its oldest section to unearth its history. Though it is approximately 2,000 years old, it has only a vague record of the various cultures that once occupied it, according to Arta. These include the Illyrians, Byzantines, Venetians and Ottomans. Today, the city is the center of Albanian Montenegro. Arta decided to look at Ulqin’s long and varied history through its built environment to understand her own relationship to the multi-layered city. Along the way she rethought approaches to research and preservation. “I’m taking this opportunity to develop a new methodology for preserving a city,” she says. Her proposal is entitled “The Forever City.”

Arta, a graduate of Stuyvesant High School, transferred to The Cooper Union from Syracuse University where she had been studying civil engineering. As a child, she had always been curious about tools and building and regularly learned from her father who was resident manager at their building on Roosevelt Island. After a year at Syracuse, she decided that she was better suited for architecture than engineering. She applied to the school of architecture after learning about it from her best friend, Laura Serejo Genes AR'14. She found Cooper “diverse and eclectic—people who don’t fit in anywhere else and find each other.”

Last summer, she took about 150 photographs of different sized tectonic elements of Ulqin—the ancient walls that encircle the city, tiles, roofs, fountains, street paving, doorways, windows. Then, as part of her research method, she examined her photographs—“I meditated over those pieces,” as she put it—and then began recreating them as drawings and models. The result is a set of detailed, carefully rendered interpretations of minute elements, from the iron bars of grates to the shapes formed by shadows on a cobblestone street. As she isolated those elements through drafting and building, she found that they subtly changed. She noticed how light and shadow created forms that were not always recognizable elements such as doorways or punched-out windows but were repeated shapes. As Arta put it in her statement for the final review, “Elements extracted from the photographs are used to develop an alphabet of the city.…” Finally, those altered elements—what she calls “shadow machines”—were re-inserted into the landscape in drawings Arta made based on the photographs. Through this method, she said, she “inserted a new moment into the moment I photographed.”

After graduating Arta will spend the summer studying for architecture licensing exams before seeking a position. Of her time at The Cooper Union, she says she learned a great deal from her fellow classmates because “we have such a collective passion for what we study.”

“A lot of my classmates keep a sketchbook; I keep a journal,” John Angelo, who goes by "J.A.," Alonzo tells us. J.A. has always used writing as a design tool. “For me, drawings and texts inform one another.” J.A. sees writing as another form of design. He writes poetry and recently won the Elizabeth Kray Memorial Prize, a writing prize given each year to a Cooper Union student, for a set of seven poems. “I’ve really gravitated towards the humanities department since my first year,” he says.

“A lot of my classmates keep a sketchbook; I keep a journal,” John Angelo, who goes by "J.A.," Alonzo tells us. J.A. has always used writing as a design tool. “For me, drawings and texts inform one another.” J.A. sees writing as another form of design. He writes poetry and recently won the Elizabeth Kray Memorial Prize, a writing prize given each year to a Cooper Union student, for a set of seven poems. “I’ve really gravitated towards the humanities department since my first year,” he says.

J.A. grew up in the Bridgeport neighborhood of Chicago and attended Walter Payton College Prep, a public school with a math and science bent. But it was his time in the national afterschool ACE [Architecture, Construction and Engineering] Mentor Program that got him thinking about design. Once a week he would meet other students from around the city at an architectural firm where they learned about the profession. Although they would work on various drawings and exercises, J.A. says it was “more about exploring what you could do with architecture and architectural forms. It was really surprising for me.”

For his thesis proposal, J.A., who was born in the Philippines, analyzed the plan by Daniel Burnham, a renowned architect of the turn of the 20th century, for restructuring the city of Manila. That plan went mostly unrealized. But J.A. is particularly drawn to the project because, as a Filipino-American who grew up in Chicago, he wants to understand how the Manila plan informed the Plan of Chicago, Burnham’s 1909 comprehensive vision for the city’s development.

Some of the preparatory work for his thesis project was done this winter when J.A. received a William Cooper Mack Thesis Fellowship to travel to Manila where he stayed with family he hadn’t seen for years. His proposal—which focuses on a network of river tributaries called esteros—offers him a clear way to think about cities important to his personal history yet through the lens of Burnham's work.

“A lot of what Burnham did in Manila anticipates the Plan of Chicago: the importance of the waterfront, the distribution of park spaces. I think the esteros were actually very important for Burnham’s plan, more so than the street grid or the monumental buildings. He had a unique vision for the waterways. He thought of it as a kind of Venice of the Orient. A lot of the legacy of American Philippines imperialism can be read through the plan as well. And the traces are all there.”

After graduating, J.A. will begin applying for work at architecture firms in New York. Eventually he would like to attend graduate school to study either architecture or poetry. "Going to Cooper," he says, "allowed me to pursue both poetry and architecture not as discrete fields but as ones that mutually inform each other."

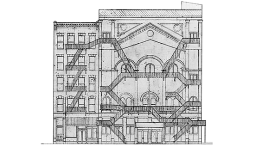

In one of its many incarnations—from farmland to skid row—the Bowery was once home to a set of vaudeville theaters. These included Miner’s Bowery Theater where, legend has it, lousy acts first got "the hook." Dustin Atlas uses the former location of the theater, which stood at 165-167 Bowery, as the site for his thesis proposal. It began with a fascination with something found everywhere in the city and yet, in a bit of collective blindness, frequently unnoticed: the fire escape. Dustin was particularly taken with the idea of a fire escape as a stage for seeing the city. “I became interested in how theatrical they are,” he said. “I mean there’s something fantastic about going through a window to enter a space, and then when you’re in that space, the city becomes a theater or a spectacle of some sort.”

In one of its many incarnations—from farmland to skid row—the Bowery was once home to a set of vaudeville theaters. These included Miner’s Bowery Theater where, legend has it, lousy acts first got "the hook." Dustin Atlas uses the former location of the theater, which stood at 165-167 Bowery, as the site for his thesis proposal. It began with a fascination with something found everywhere in the city and yet, in a bit of collective blindness, frequently unnoticed: the fire escape. Dustin was particularly taken with the idea of a fire escape as a stage for seeing the city. “I became interested in how theatrical they are,” he said. “I mean there’s something fantastic about going through a window to enter a space, and then when you’re in that space, the city becomes a theater or a spectacle of some sort.”

With that in mind Dustin began researching the placement of fire escapes on theaters in New York. When he came across a drawing of Miner’s Bowery Theater, he was struck by the integration of the fire stairs into the design of the building’s front elevation. They are set at angles that play off of the pediment on the theater’s façade and, intentionally or not, mimic the crisscross support structure of the elevated train that ran along the Bowery. During further research he found out that the theater was greatly damaged in a fire on November 7, 1922. Dustin, who has been working with a Broadway set designer in his spare time, conceived of the fire as an inversion of the theater experience: the house of spectacle became a spectacle itself.

At that point, Dustin decided that the physical manifestation of his research would take the form of a theater comprised only of fire escapes. This armature would create an outdoor space at the former Miner Theater location that would blur not only the boundaries between actor and spectator, but building and city. Taking inspiration from Lina Bo Bardi’s Teatro Oficina in São Paulo, Brazil, he imagined a theater where the back-of-house is indistinguishable from its stage. Formally, this works particularly well since the iron members of fire escapes resemble theater scaffolding, which are often hidden. Instead, Dustin proposes a contemporary theater space that celebrates the industrial and mechanical structure of its own operation.

While researching theater and theater architecture, Dustin read about the role of puppets and masks as mediators between audience and performer: instead of communicating directly, the audience and the actor meet each other in the space of the puppet. Dustin thought that a wall-less theater with metal scaffolding as the only threshold between theater and street would function as a liminal meeting place, much like a marionette. The walls would be manipulated by performers and audience members alike. "I wasn’t designing a puppet theater but a theater puppet," he says.

After graduating, Dustin, who comes from a family of architects and engineers in San Diego, will teach in Be’er Sheva, Israel after winning a teaching fellowship. He has been inspired by his work as a teacher of kindergarten students at New York’s Jewish Community Center every Saturday afternoon. “There are a lot of options I want to explore,” he says, but he feels particularly drawn to teaching. “I’d love to give that a try—to figure out how my design background can be used to facilitate the learning process.”