$4 Million Bequest to Keep Innovation Alive

POSTED ON: April 4, 2024

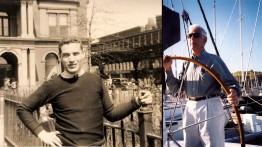

In an interview about his greatest life lessons, Ed Durbin (1927–2015) talked about the changes in the field of engineering epitomized by a move he made from New York to Los Angeles in the mid-1960s: while East Coast companies wouldn’t hire anyone who had left a job before five years, on the West Coast anyone who stayed at a job for more than five was considered unambitious. “The speed of life changed, and the value of innovation and novelty became clear, and I think I absorbed that.”

Durbin, who graduated from The Cooper Union in 1948 with a degree in electrical engineering, invested in the engineering school and its students during his lifetime by establishing the Edward Durbin and Joan Morris Innovation Fund for the Albert Nerken School of Engineering. The Durbin Fund, a generously sized endowment, is designed to promote research, improve pedagogy in STEM disciplines, and sponsor entrepreneurship. Now, The Cooper Union is the recipient of a bequest from the estate of Edward Durbin that has sparked a fundraising campaign matching all donations, no matter the size, up to $4 million. The campaign’s intention is to encourage others who benefitted from Cooper, as he did, to support Cooper today and into the future.

“The education I was given by the school was the cornerstone of my whole career, for which I am everlastingly grateful, and I have always tried within my means to say thanks for the head start,” Durbin, who had been vice chairman and director of Kaiser Aerospace, said in 2015.

The Durbin-Morris Innovation Fund initially supported Invention Factory, an intensive summer program that challenges undergraduates to invent a product and learn the essentials of patent law. He told the founders of the program that “the desire to stimulate students to be creative and improve their chances for enhancing their careers was the inspiration for the Invention Factory program.” (Durbin underwrote a similar program at the Bronx High School of Science.)

“The Durbin endowment has provided resources that have allowed us to modernize our curriculum and provide our students with experiences that better prepare our graduates to succeed in a dynamic and increasingly complex world,” said Barry Shoop, dean of the Albert Nerken School of Engineering. The Durbin Fund underwrites the Dean’s Educational Innovation Grant, supporting the school’s expanded summer study abroad program, and a special summer project to reimagine the engineering capstone experience by developing deliberately interdisciplinary projects.

Durbin’s story began in Manhattan, as the youngest of four children. His parents were immigrants from Eastern Europe who ran a laundry where he and his siblings would work when time permitted. In many ways, Durbin’s older siblings mentored him—especially his brother, Enoch, who tutored Durbin in an array of science concepts while he attended the newly opened Bronx High School of Science. Enoch himself studied engineering at City College and enjoyed a career as a professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at Princeton University for 40 years. Durbin matriculated at Cooper in 1945 when he was 16, graduating in three years in an accelerated program while working in his parents’ laundry on nights and weekends.

Directly after college, Durbin started work at Rand Sperry in Great Neck, New York while working on his master’s degree. There he made major contributions to LORAN radio navigation for ships while raising two daughters with his first wife. According to his daughter, Meg Durbin, he earned a little extra money as the fix-it guy for his apartment building, whose tenants would bring him various electronics to repair. Durbin left Sperry after almost 20 years at work: he was all of 39 years old.

Still young and wanting new challenges, he headed to Los Angeles to work at Teledyne. The year was 1966, and the West Coast proved to be a good place for an engineer looking for an open-minded environment that encouraged innovation. Nine years later, he moved to the Bay Area to help found Kaiser Aerospace, shaping the company from its inception.

While highly dedicated to his work, Durbin spent much of his copious energy on sailing, a hobby he took up in Long Island. He won countless races in all classes of boats. Though an affable presence with family, Durbin transformed into a formidable, commanding presence once he took the role of skipper. “He poured his managerial skills and tinkering talents into the yacht clubs he joined and led,” Meg said.

Recalling his love for all kinds of hands-on projects—from sewing to car repair—Meg describes many hours spent talking with her father as they rebuilt the engine of his 1965 Corvair. He did pause his auto tinkering one day years earlier, when his young daughter announced she was running away. Her dad’s response? “Where shall we go?” and the two headed to an ice cream shop. An avid tailor—a skill learned from his mother—he made and mended clothes, including his grandson’s tuxedo tie, which he fashioned to match the dress of the boy’s prom date.

In the last years of his life, he was still a fan of movement and discovery. Having flown across the country innumerable times, he decided to take a cross-country road trip. A car relay took him from his home on the West Coast to Nova Scotia: one relative would drive him for one leg of the journey, then another would join for the next portion of the trip. Along the way, he reconnected with family across the continent. The Durbin Family dubbed the trip “The Grand Amble.”

In addition to his philanthropy at The Cooper Union, Durbin set up a trust for children of immigrants. Asked why he felt it important to fund this group, he pointed out that immigrants have extra hurdles to overcome—language barriers and “old world” values that might put more emphasis on going to work before education. “There were a couple of rough spots in going to school when it was obviously a strain on my parents because I could not work in the store,” he said. “And it seemed like there must be kids out there who never did get to school because their parents couldn’t afford to have them not work. And I thought that would be a terrible loss to the individuals.” Thanks to Durbin’s gift, many Cooper students don’t need to choose between paying for family bills or their education. It’s a gift that will continue to make an impact for generations of talented students.