Saturday Program at 50

POSTED ON: April 10, 2019

A shorter version of this article was published on this website in December 2018. This fuller version was published in the Spring 2019 issue of At Cooper magazine.

That The Cooper Union’s Saturday Program has been around for decades, providing thousands of underserved local high school students the chance to get a taste of art school at no cost to them, has never been in doubt. But information about how it originated had been lost for some time. “I’ve always heard that it started in 1968,” said Marina Gutierrez A’81. She has directed the program for over 30 years, but had no record of who initially founded it or why. With the milestone anniversary of the Saturday Program this year, it seemed like a good time to dig deeper.

According to Cooper lore, the program known by its current participants as SatPro was started in the midst of the great upheavals of the late 1960s, when students and faculty alike were questioning the role of higher education in replicating social and economic disparities. But there is little documentation of its early days.

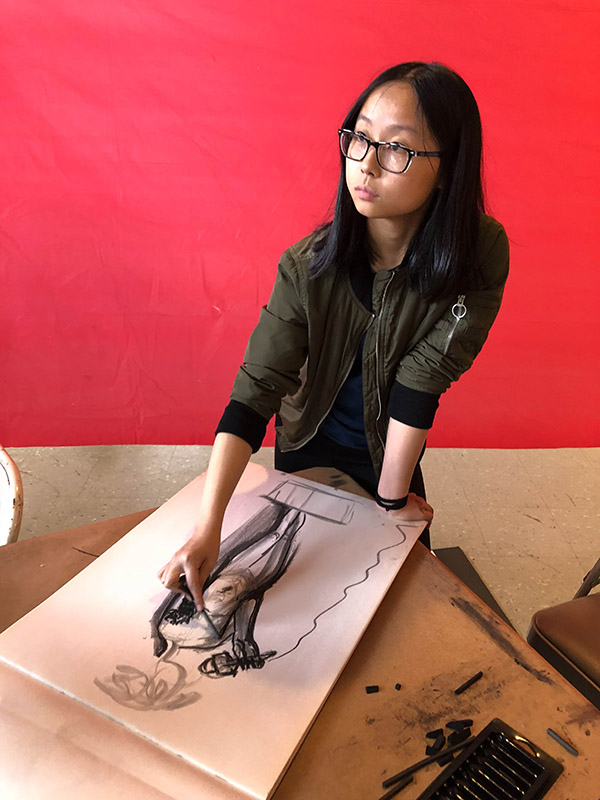

What is well-documented is that the program has been extraordinarily successful in launching the artistic and academic lives of more than 15,000 talented high school students over the years. The Saturday Program has been a resource for teenagers from New York City public high schools who care about art and architecture; they travel across the city to spend their Saturdays immersed in paints, charcoal, words, and clay for an experience that has changed so many lives.

This much is also certain about the program: it has always been tuition- free, mirroring the mission of The Cooper Union in its effort to provide education to the underserved. Its admissions policy is need-blind, but limited exclusively to New York City public high school students, with an eye toward reaching people from minority backgrounds. SatPro’s core mission resonates with many of its financial support- ers, such as Richard Lincer, former chair of the Board of Trustees. “The reason my wife and I support the program is that we believe that it so well exemplifies Peter Cooper’s fundamental objective in establishing The Cooper Union—to make education available to those who would not otherwise have access to it.”

Gutierrez finds parallels between the era of the program’s founding and today’s political and eco- nomic climate. “With so many cuts to arts programs in public schools, we provide one of the very few outlets for free classes and materials for students who want to explore art and architecture but can’t afford to pay for private classes. We find ourselves again on the front lines, confronting the unraveling of the social contract when it comes to educational access and equity.”

Prominent backers from the worlds of finance and art have tried to bridge that gap by giving significant support. In 2013, Jeffrey Gural, a trustee at the time, granted a million-dollar gift to the Saturday Program, to be distributed over 10 years. The renowned art critic Lucy Lippard recently wrote in an email, “I’ve known Marina for years through her art and political groups we shared. I much admire what she does with the Saturday Program and will continue to support it as long as I can afford it!” Others offer their time. Tomie Arai, Robin Holder, Marilyn Nance, David Rios Ferreira, and Anton van Dalen are a few of the artists who have worked with the program. SatPro students can be seen on a studio visit in a documentary about van Dalen, The View from Avenue A (1985). They can also be seen in a recent video visiting the studio of Jack Whitten A’64; he offered that invitation annually to the students of SatPro until his death in 2018.

Richard Lincer points out another gap the program fills. “Despite the availability of scholarships at Cooper and at other colleges and universities that might make attendance affordable, one of the problems is that many talented students in New York City high schools are not aware of these programs and don’t have the support to enable them to successfully apply and prepare for college. The Saturday Program—in not only helping the students develop their portfolios but also supporting the development of their writing and assisting in college applications—wonderfully fulfills this need. Having attended some of the year-end shows and celebrations, we have been so very impressed with the level of engagement of the students and the Saturday Program leaders and volunteers.”

Mike Essl A’96, dean of the School of Art, agrees that the program still fills an educational gap that has widened, particularly in arts education. “The Saturday Program demonstrates to young artists that their voices count and gives them the means to articulate their ideas. The program is needed now more than ever.” Another of SatPro’s long-standing traditions is the integration of current undergraduates as instructors. When Gutierrez joined the staff as a second-semester freshman, the program was still fully student- run. During her senior year at Cooper she became the program’s student director. She and the student staff, which also included Doug Ashford A’81, who continues to teach in the School of Art, decided to ask Bill Lacy, the col- lege’s president at the time, to make the director a paid staff position. He agreed.

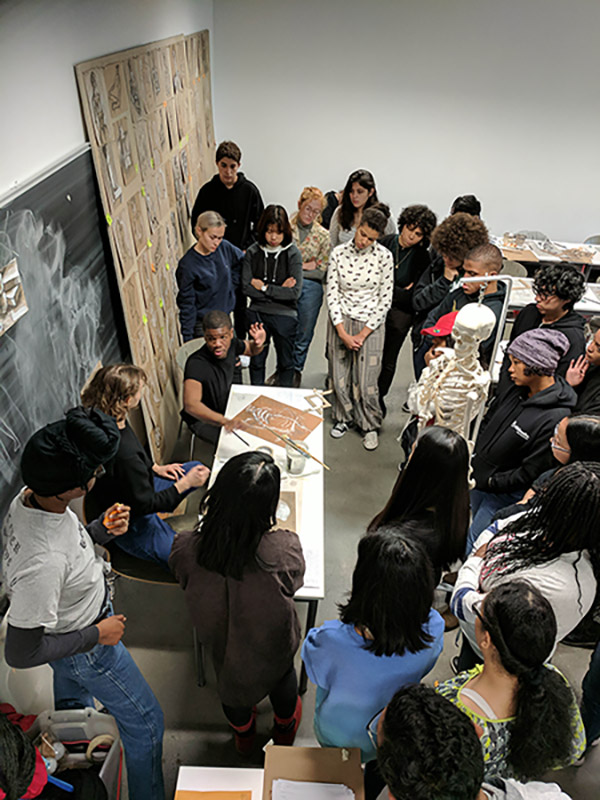

Since then the program has expanded while staying true to its basic tenets. Today SatPro offers classes in painting, sculpture, sound composition (the only such free course in the city), architec- ture, and graphic design, in addi- tion to the drawing classes initially provided in its earlier days. And the courses are still taught by art, architecture, and engineering students of The Cooper Union, Marina Gutierrez under the guidance of a staff of working artists.

Even students who decide not to pursue the arts gain an appreciation for learning; this is reflected in the rate of SatPro alumni who go on to college—approximately 85 percent, some of whom gain entry to The Cooper Union. One of them, Vaughn Lewis, currently a fifth-year architecture student, applied to Cooper after studying in the Saturday Program. “That high school experience opened up a whole avenue of possibilities for me,” he says. “I learned about The Cooper Union’s architecture program and knew that was where I wanted to study. The Saturday Program helped me learn to think abstractly and analytically to do my best work. I also realized what I needed to know to be a competitive student in the application process.” Vaughn started teaching in the program because it was a way to share that experience with other high school students.

One of the most valuable courses offered through the program is Portfolio Prep, which helps students build a strong selection of work to submit when applying to art schools. Like all the other courses, Portfolio Prep is taught by students at The Cooper Union. “The program exponentially expanded my understanding of what art could be,” says Jairo Sosa A’17, a Bronx native who attended the Saturday Program during high school. Now he has returned to the program as the acting office coordinator and instructor for Portfolio Prep. “Once those floodgates are opened, Portfolio Prep pushes students to articulate what role they want to play, and helps them clarify what they want to develop in themselves and become aware of the skills they already possess.”

At various points in its history, the program has been criticized for following a student- as-teacher model. Detractors argued that such an arrangement could not deliver a worthwhile education and that the open- enrollment policy of the program would by definition lower the quality of work produced. That assessment, however, is countered by supporters who argue that all students should have the chance to make art, not least because many have not had any other opportunities via the public school system. In fact, the program has consistently positioned itself as an alternative to the exclusivity of an atelier education. Former dean of the School of Art Robert Rindler AR’70 recalls the early days of the program as an inherent critique of unequal access to quality education. He says that from its inception, the Saturday Program challenged “the institutional relationship between authority and responsibility.”

That appraisal is in keeping with the era of its presumed founding. Along with the highly publicized student protests in Paris and Berkeley, a standoff took place in the spring of 1968 between Columbia’s students and administration. New York City’s high school students directly felt the impact of these debates when the city’s public school teachers went on strike for more than seven weeks, the result of communities fighting for local control of school decision-making. Out of this milieu was born the Saturday Program.

But the question remained— who, exactly, was behind it?

Efforts to reach out to specific graduates of that era yielded nothing specific. So the communications office resorted to sending out a mass email to all alumni from the School of Art who graduated in 1968 or ’69, appealing for information.

Several wrote back to say they were involved in the early days of the program, including Norman Askinazi A’69, who identifies himself as one of SatPro’s founders, but recalls little about its inspiration.

Then there came this missive from Robert Van Nutt A’69: “Your email came to the right place for the history you are looking for. The Saturday High School Workshop program was my brainchild. It was inspired by two things: one was New York University’s High School Painting Workshop, which I attended in 1964–65. The other was the New York City teachers’ strike of 1968.” Mystery solved.

With that, it soon became clear that a founder of the program was living just minutes away in the West Village. He had no idea that the Saturday Program was still around. He and Gutierrez decided to meet last December, and soon he made the short crosstown trip to give her the whole story—and see exactly where his efforts had led 50 years later.

Van Nutt arrived in the Saturday Pro- gram’s offices just as Gutierrez and her staff were packing to move their studio and classroom, overflowing with art supplies, books, and miscellany, including a manual typewriter and a stack of old LP records. Gutierrez ushered him in, while some of the younger staff and students took him in with palpable awe as if witnessing a being from another dimension. And in a sense it was a fair reaction: over the years, there had been so much talk about the initial days of the program that when a founder from 1968 walked in the door, it hardly seemed possible.

They talked about their dedication to art and to collaboration. Gutierrez has described the Saturday Program as one “tailored to a wide range of student skill level and personal interest. Some of the enrolled students are entirely new to visual arts training, but are curious to explore the visual arts as an avenue for self-expression.” She finds that watching young people, especially those who feel alienated from traditional classroom education, discover art injects energy and ideas into her own artwork.

Van Nutt thrives on input too, especially from his wife of almost 50 years, Julia, with whom he frequently collaborates. A highly accomplished artist, Van Nutt has been a painter, set designer, woodworker, costume designer, model maker, graphic designer, and children’s book illustrator. He told of how he had traveled from northern New Jersey to New York University during his high school years to study and to be ensconced in a city where he could learn so much about art.

Later, as a junior in The Cooper Union’s School of Art, he realized that the public school strike could be an opportunity. Why not offer high school students, sitting at home with no classes, the chance to learn art skills taught by Cooper’s undergraduates? He took his pro- posal to the administration, which had no truck with the idea. (“We did everything ourselves—it didn’t cost the school a thing,” Van Nutt noted.) After classes were designed and students were drafted from local schools, the program became a hit—so much so that Van Nutt, Askinazi, Fred Brandes A’69, Evelyn Persoff A’69, Lia Di Stefano A’69, Jack Freeman AR’69, and Ed Hauben AR’69, all members of the first staff, kept the courses running even after the strike ended. And with that, the Saturday Program was founded. “On Saturday morning high school kids would come in from the community to participate. I loved working with these motivated people,” recalls Askinazi.

Although the students got great satisfaction from teaching high schoolers the skills they themselves had recently learned from Cooper’s professors, they didn’t imagine that the program they started would have much longevity. “We had no idea it would be anything,” Van Nutt told the assembled current SatPro staff, clearly pleased at the beautiful chaos of the room, if also feeling a bit shy in the face of all the attention. Like so many of the Saturday Program’s students, he came from a family of modest means and needed to get creative to find a way to make his art education happen. “I started the Saturday Program because I’d been a student in a similar program at NYU when I was in high school,” Van Nutt told the current generation. “I’d use the drawing pads that rich kids had just left in their lockers at the end of the school year.” The group laughed in recognition at the familiar make-do attitude that has also been a hallmark of the Saturday Program. Van Nutt looked around the room. “I never thought it would still be running 50 years later.”