Scholarship of a Different Feather

POSTED ON: November 28, 2012

Heidi King, Adjunct Instructor of the Humanities and Social Sciences faculty, has a new book out that combines scholarship and sumptuousness into a single, ravishing package. Peruvian Featherworks: Art of the Precolumbian Era (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; 232 pp.; $60) features masterworks of textiles and objects in other materials such as wood and hide, decorated with intricate and ornate mosaic made of exotic bird feathers. Many of the works in the book have never been published or exhibited.

"It is rare for the Metropolitan Museum to publish a book unrelated to a current exhibit," says Heidi King, a specialist in Precolumbian Art who is a Research Associate in the Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. She curated an exhibit there in 2008, "Radiance from the Rain Forest: Featherwork in Ancient Peru." The exhibition did not have a catalog, but Heidi King convinced the Met that a more expansive publication on the subject would fill a gap in the literature on ancient Peruvian textile arts. Consequently many more pieces are illustrated in the book than appeared in the 2008 exhibit.

"It is rare for the Metropolitan Museum to publish a book unrelated to a current exhibit," says Heidi King, a specialist in Precolumbian Art who is a Research Associate in the Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. She curated an exhibit there in 2008, "Radiance from the Rain Forest: Featherwork in Ancient Peru." The exhibition did not have a catalog, but Heidi King convinced the Met that a more expansive publication on the subject would fill a gap in the literature on ancient Peruvian textile arts. Consequently many more pieces are illustrated in the book than appeared in the 2008 exhibit.

King, who has taught here for almost ten years and whose current class, Art and Architecture of Ancient Peru filled quickly, does not specialize in featherwork or even textiles. "When working with Precolumbian art in an art museum you have to be a generalist," she says. King wrote the introductory essay, an overview summarizing what we currently know about ancient Peruvian featherworks based on the archaeological record, considerations of iconography and techniques used in the manufacture of the works. Other contributors include textile experts who discuss feathered textiles made by different cultures, and archeologists who excavated feathered textiles. One essay, written by a textile conservator at the Met, describes the techniques used to create feather mosaic on textiles and objects in other materials. Textiles, for example, are covered with feather mosaic by first tying feathers individually along strings and then sewing the feather strings to the cloth in overlapping rows, ‘shingle fashion’ starting from the bottom.

"We know that feathers were considered a precious material on a par with gold, shells, and semi-precious stones in ancient Peru," King says, "and one of my conclusions is that feathers may actually have been the ultimate luxury material." It is easy to see why from the book. For their featherworks the ancient Peruvians seem to have preferred the vibrantly colorful feathers of rainforest birds rather than those of local species which are generally more muted in tone, according to King. She believes that feathers were chosen primarily because of their color “although it is reasonable to assume that the birds the feathers came from also had symbolic associations; but bird symbolism – and color symbolism for that matter – is currently not well understood."

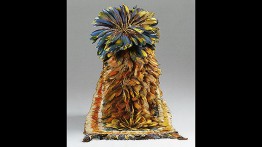

Contrary to expectations, many surviving featherworks look as fresh as when first made. The entire second half of the book contains plate after plate of brilliantly colored works like the tabard, a men's garment similar to a tunic, covered with thousands of deep vermillion and bright yellow macaw feathers. Other objects include miniature dresses, like one with a red and green checker pattern used in close-up on the book's cover. The design skills of the artists seem unlimited by their medium, producing complex geometric patterns as well as depictions of animals and occasionally human figures. Even going beyond flat representation, one remarkable pin duplicates a bouquet of flowers in a vase, complete with a buzzing insect. Appealing to scholars as well as anyone who loves beautiful objects, Peruvian Featherworks will lift your spirits.