New Collaboration Between HSS and School of Art

POSTED ON: October 27, 2021

This fall two professors—one from the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences (HSS) and the other the School of Art—introduced a new course that combines art history with art making. Raffaele Bedarida, HSS associate professor, and art historian who studies 20th century Modernist art movements in Italy, has teamed with Cristóbal Lehyt, assistant professor in the School of Art, to offer Sculpture: Arte Povera (HTA 313 F1/FA 393A I). The course uses Arte Povera, an art movement that originated in Italy in the mid-1960s, as a starting point for analysis of issues critical to artists then and today such as the role of capital in making art and the source of materials. “One of the questions that I’ve always asked myself, said Bedarida, “was what are the dynamics of [studio] critiques and how to bridge the gap [to history classes]. When this came up I was excited about the same group of students in the same space with a practicing artist and an art historian.”

The course came about quite organically, said Bedarida: he’d been talking to Lehyt, who mentioned that Arte Povera, a subject Bedarida has written about extensively, comes up with some frequency in his sculpture classes. They realized that a class jointly taught could give students an excellent medium for grappling with very pressing issues. Lehyt said, “In sculpture classes there’s a necessity for materials to matter and for the last four or five years there is this apocalyptic sense that the world is going to end because of the climate crisis. Arte Povera, with its emphasis on materials, appeals to students who are looking to have some sense of control. Arte Povera found a way for us to understand objects and matter in the world.”

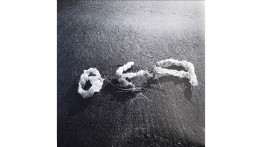

Literally translated as “poor art,” Arte Povera grew out of the writing of Germano Celant, who proposed that artists approach materials not only for their aesthetic features but for their multi-sensory possibilities, activating them through performative actions, and considering their ethics. Arte Povera artists mined “everyday” materials, anything from discarded household goods to sticks and soil; they included food and living animals as part of their work; and combined them with signs of modern life such as neon lights or aluminum foil. Their working methods included knitting, burning, and various kinds of chemical reactions, in addition to carving, drawing, and traditional studio practices. And their exhibitions spaces were not limited to art galleries, often inhabiting urban spaces, beaches, woods and more.

For Celant, who died last year from Covid-19, the goal was to explode traditional boundaries in order to expose and escape the commerce-driven aspects of the art world. The concept moved well beyond Italy’s borders thanks to Celant’s canny understanding of how the concept of “poverty had acquired positively ethical connotations in Europe as well as the United States,” as Bedarida wrote for an essay entitled “Transatlantic Arte Povera.” In fact, the movement’s ideas had great currency in Latin America, influencing artists such as Flávio Motta, Antonio Dias, and the architect, Lina Bo Bardi. They were drawn, in part, to Arte Povera’s valorization of vernacular objects and arts.

Teaching the class across schools posed some difficulty in determining how credit would be distributed, which is usually determined by each of the degree-granting schools. Besides the obvious pedagogical advantages of an art historian teaming with an artist, the course has laid the groundwork for future collaborations by providing an administrative precedent. HSS Associate Dean Nada Ayad said, “Part of the goal for the Arte Povera class is to establish clear protocols and reasonable precedents so that we could do this in the future if there is interest. Having a full class co-taught by two professors from two different schools is not only an incredible asset for our students, but also a great model of collaborative thinking and pedagogy.”