Pullman Porters: A Legacy of Resilience, Resistance, and Progress

Sun, Feb 21, 2021 12pm - Fri, Mar 19, 2021 5pm

Installation detail of the Pullman Porters exhibition

In honor of Black History Month 2021, The Cooper Union presents this look at the journey of the Pullman porters. The below posters were designed to fit into the windows on the West side of the Foundation Building, facing the street. The text is extracted from the posters.

Employed by industrialist George Pullman shortly after the end of the Civil War, Pullman porters served wealthy and middle-class travelers riding in high style on the nation’s rapidly expanding rail lines. Despite low wages and abysmal working conditions, these porters became key sources of financial and cultural support for Black communities around the country. They went on to establish the first African American labor union in the U.S. and were central to the formation of what would become the Civil Rights Movement.

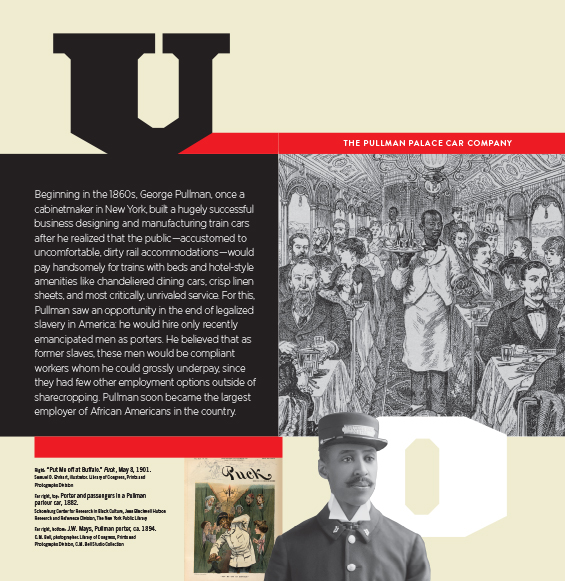

Beginning in the 1860s, George Pullman, once a cabinetmaker in New York, built a hugely successful business designing and manufacturing train cars after he realized that the public—accustomed to uncomfortable, dirty rail accommodations—would pay handsomely for trains with beds and hotel-style amenities like chandeliered dining cars, crisp linen sheets, and most critically, unrivaled service. For this, Pullman saw an opportunity in the end of legalized slavery in America: he would hire only recently emancipated men as porters. He believed that as former slaves, these men would be compliant workers whom he could grossly underpay, since they had few other employment options outside of sharecropping. Pullman soon became the largest employer of African Americans in the country.

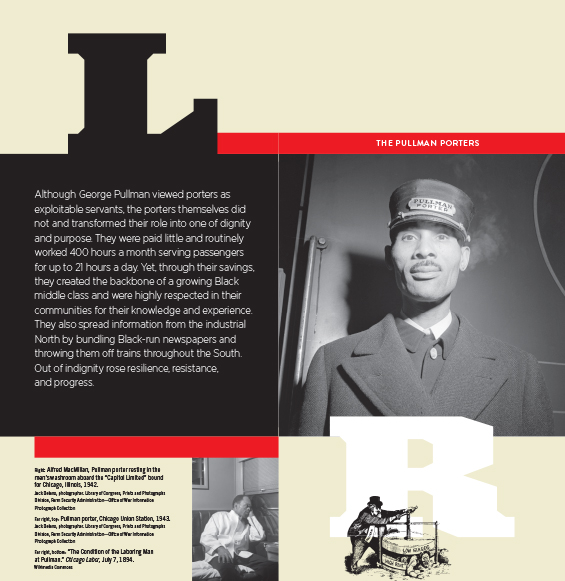

Although George Pullman viewed porters as exploitable servants, the porters themselves did not and transformed their role into one of dignity and purpose. They were paid little and routinely worked 400 hours a month serving passengers for up to 21 hours a day. Yet, through their savings, they created the backbone of a growing Black middle class and were highly respected in their communities for their knowledge and experience. They also spread information from the industrial North by bundling Black-run newspapers and throwing them off trains throughout the South. Out of indignity rose resilience, resistance, and progress.

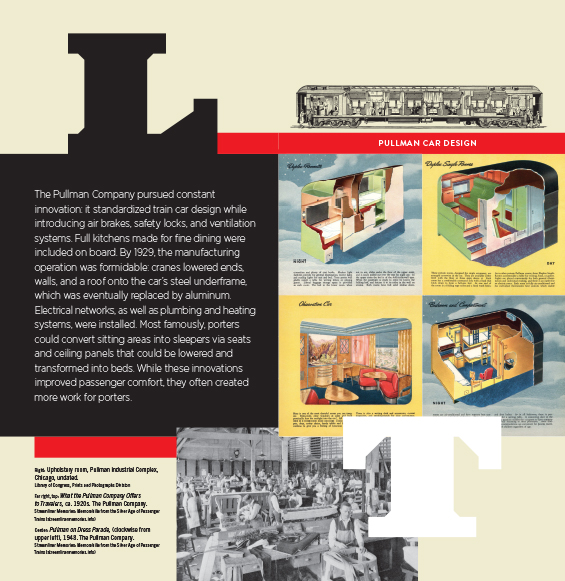

The Pullman Company pursued constant innovation: it standardized train car design while introducing air brakes, safety locks, and ventilation systems. Full kitchens made for fine dining were included on board. By 1929, the manufacturing operation was formidable: cranes lowered ends, walls, and a roof onto the car’s steel underframe, which was eventually replaced by aluminum. Electrical networks, as well as plumbing and heating systems, were installed. Most famously, porters could convert sitting areas into sleepers via seats and ceiling panels that could be lowered and transformed into beds. While these innovations improved passenger comfort, they often created more work for porters.

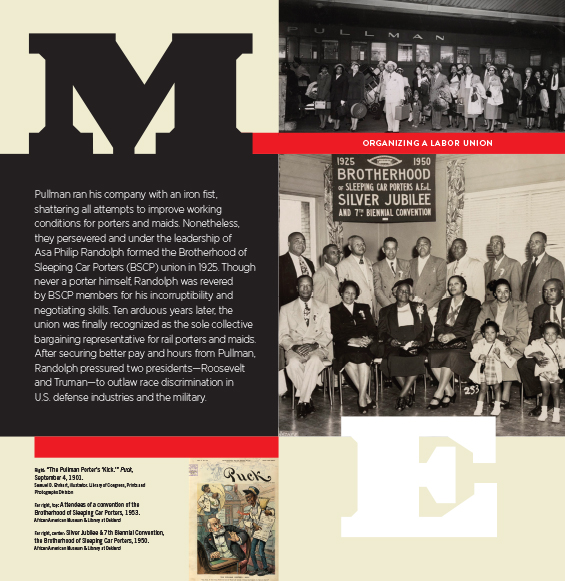

Pullman ran his company with an iron fist, shattering all attempts to improve working conditions for porters and maids. Nonetheless, they persevered and under the leadership of Asa Philip Randolph formed the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP) union in 1925. Though never a porter himself, Randolph was revered by BSCP members for his incorruptibility and negotiating skills. Ten arduous years later, the union was finally recognized as the sole collective bargaining representative for rail porters and maids. After securing better pay and hours from Pullman, Randolph pressured two presidents—Roosevelt and Truman—to outlaw race discrimination in U.S. defense industries and the military.

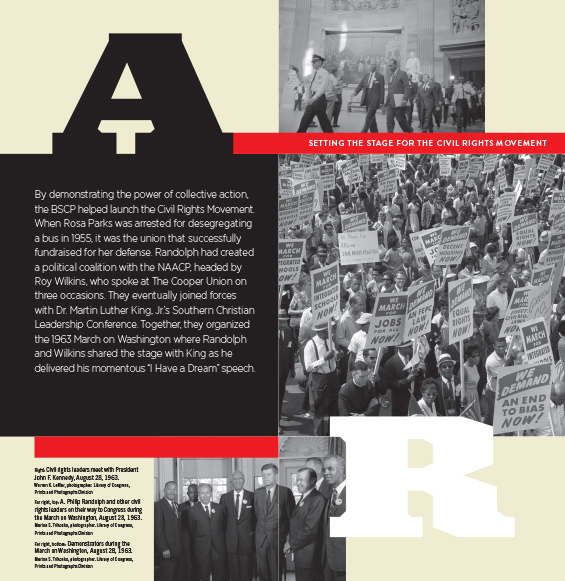

By demonstrating the power of collective action, the BSCP helped launch the Civil Rights Movement. When Rosa Parks was arrested for desegregating a bus in 1955, it was the union that successfully fundraised for her defense. Randolph had created a political coalition with the NAACP, headed by Roy Wilkins, who spoke at The Cooper Union on three occasions. They eventually joined forces with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Together, they organized the 1963 March on Washington where Randolph and Wilkins shared the stage with King as he delivered his momentous “I Have a Dream” speech.

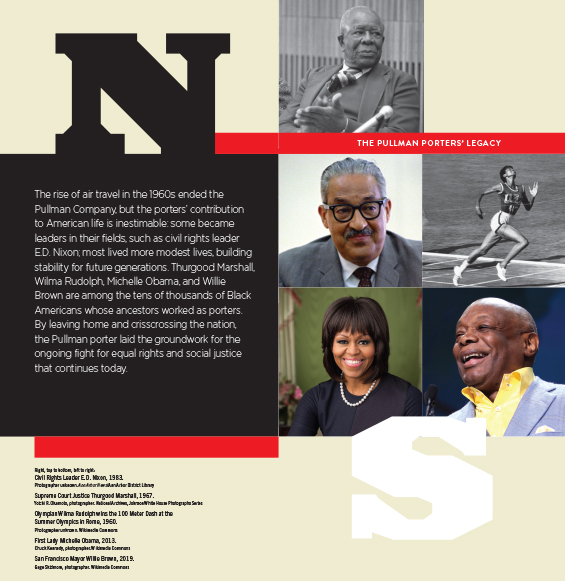

The rise of air travel in the 1960s ended the Pullman Company, but the porters’ contribution to American life is inestimable: some became leaders in their fields, such as civil rights leader E.D. Nixon; most lived more modest lives, building stability for future generations. Thurgood Marshall, Wilma Rudolph, Michelle Obama, and Willie Brown are among the tens of thousands of Black Americans whose ancestors worked as porters. By leaving home and crisscrossing the nation, the Pullman porter laid the groundwork for the ongoing fight for equal rights and social justice that continues today.

ROY WILKINS ON FREEDOM, FRANCHISE, AND SEGREGATION

Excerpted from his speech in

THE GREAT HALL OF THE COOPER UNION

February 1, 1960

Mr. Chairman, and ladies and gentlemen, it is a privilege to have a small part in the celebration of the centennial year of The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, and to speak here in this famous forum where so many issues of importance to our nation and to the world have had an airing.

In many a year since the founding of our country, it must have seemed to the anxious students that freedom of speech and freedom of assembly were about to be curtailed if not abolished. The tensions that develop with wars, the fervors distilled in political and economic conflict, and the emotions stirred by debate over human rights here and abroad have threatened these and other precious freedoms from time to time.

The Bill of Rights has escaped often by the skin of its teeth. The courts, which have dared to interpret it and other clauses in our Constitution, have had to meet and defeat challenges of greater or lesser intensity. Through it all, America has lived and grown, meeting and overcoming crisis after crisis.

And I suggest that her survival and the preservation of her credo of individual liberty and of governing by consent of the governed, have been due in substantial measure to the fealty accorded these ideals by Cooper Union and by similar institutions throughout our land.

I have a peculiar interest in this place and this celebration, and in this topic. It was just 50 and a half years ago that here in this Great Hall was held a mass meeting which helped to bring forth the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. On the night of May 31, 1909, Judge Wendell Phillips Stafford of the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia presided at a mass meeting here at which John Milholland was one of the speakers.

The meeting was part of a two-day conference described in The New York Times of that day as one, and I quote, “to consider the uplifting of the negro.” A commentary on those times and a small indication of the distance we have come may be found in a headline which the Times of June 1, 1909, placed over its account, and the headline stated, “Whites and Blacks Confer as Equals.” In the story of The Cooper Union meeting, the Times said, and I quote, “Cooper Union was three-quarters filled with men and women of both races. Negro men and white women sat side by side. On the platform were leaders of the movement—both black and white.”

The conference committed itself to a union of the races in the public schools, as against segregation of the Negroes as is now the case in the South, thus disposing of the popular 1956 argument in the Deep South that the NAACP thought up school desegregation the day before yesterday. Resolutions adopted at the final meeting of the 1909 conference have a familiar ring today—demanding the enforcement of the 14th Amendment, demanding equal educational opportunities, and demanding the right to register and vote under the 15th Amendment. Lynching was scathingly denounced.

The conferees were called radicals and Booker T. Washington, Seth Low, Andrew Carnegie, and other conservatives would have none of the meeting. When the gavel fell upon the last speech, the continuation committee, named by a Chairman Charles Edward Russell, began the formal organization of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Russell was to be a member of its board of directors until his death, and Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois was to be its editor and spokesman and board member for 25 years, until his resignation in 1934.

Thus, The Cooper Union centennial has a special significance for the NAACP in the light of the stormy desegregation debates of the past 10 years, and especially those of the six years since the Supreme Court’s ruling on racially segregated public schools.

The scheduling of this discussion tonight by this speaker is clue enough to the continuing independence and vigor of a hale centenarian. May Cooper Union live and continue to mold sinewy thought through its second hundred years and more.

Located at 7 East 7th Street, between Third and Fourth Avenues