Snarkitecture: The Collaborative Effect

POSTED ON: August 1, 2011

Daniel Arsham (A'03, right) and Alex Mustonen (AR'05)

In 1993, the architect Stephen Holl and the artist Vito Acconci famously collaborated on the renovation of New York City’s Storefront for Art and Architecture, creating a playful, puzzle-like façade of variously shaped, rotating panels opening onto Kenmare Street.

This spring, almost 20 years later, Storefront underwent another improbable transformation—this time orchestrated by a young, Brooklyn-based interdisciplinary studio called Snarkitecture. The studio’s partners, artist Daniel Arsham (A’03) and architect Alex Mustonen (AR’05), packed the interior with large polystyrene blocks, then excavated the space with hand tools to create a wholly unexpected, all-white, sculpted interior somewhat akin to a glacial cavern.

This reversal of the typical way of making space comes as no surprise to those who have followed Arsham and Mustonen’s work over the last few years. From stage and furniture design to temporary installations and performance projects, they defy expectations of surface, material and form.The result is a portfolio of novel projects—often involving the re-invention of existing structures or designs—made possible by the combination of their unique skill sets.

“Some of my proposals are almost ridiculous,” says Arsham, 30, whose solo work has shown in Miami, Paris, London and Amsterdam. “But, at the same time,maybe they’re not something that an architect would propose.When that happens, it’s up to Snarkitecture to figure out how to make it work.”

“We think there is something unique about a sustained collaboration between an artist and an architect,” says Mustonen, 29. “Coming from art and architecture backgrounds, there are overlaps and differences, but the collaboration between disciplines is at the core of the practice.”

As demonstrated by the Storefront project, known as DIG, that collaboration drives Snarkitecture to not only think outside the box, but to also re-imagine the box itself. “A lot of the aesthetic language that the practice uses comes from these artworks that I’ve done—pieces that manipulate the surface of architecture in ways that cause it to stretch, melt, or appear to be wrinkling,” says Arsham. “It takes this very rigid surface that we know and causes it to do things that it is not supposed to do.”

“People, especially children, are drawn to our work because it manipulates architectural form,” says Mustonen. “It is this very uncanny sensation—it’s something that they know, so they have expectations of it, they are familiar with it—and then their familiarity with it is broken, and it is something different. It draws you in, and it is also repels you in a way.”

Arsham and Mustonen first met as students at The Cooper Union, and Arsham soon sought out Mustonen to help on a few art projects that had more of an architectural bent. Arsham had come to New York after growing up in Miami, while Mustonen had grown up in Connecticut. For both, Cooper Union was an easy choice. “Everybody wanted to go to Cooper because it

was considered the best school,” says Mustonen. “And being in New York was key to me.”

“It was always the place I heard about in high school—it was definitely the place to go,” says Arsham, who notes that the ability to not specify a direction allowed him to work in a variety of media that he uses to this day, including painting, sculpture, video and printmaking. He points to Doug Ashford and Walid Raad as influential professors and advisors.

“In the architecture school, the purpose is to learn how to draw and learn how to think,” says Mustonen. “It excels on the development of conceptual and critical faculties.”He says his first professor, Raymond Abraham, and fourth-year professor Diane Lewis were particularly influential.

The duo first collaborated when Arsham was working on a project based on Le Corbusier’s “Dom-ino” house. “I needed plans to construct the model,” says Arsham, “but I didn’t know how to draft—at all. I asked Alex if he would draft it for me, and he did it by hand.” After graduation, Arsham returned to Miami, and was soon commissioned to create a permanent fitting room installation for the fashion retailer Dior. Arsham’s design included a mirror recessed behind the surface of a wall—and he brought in Mustonen to assist with the implementation of the design in Paris and Los Angeles.

“Following that project, there were a number of others I was approached about that were even closer to architecture,” says Arsham. “Certain aspects of the projects were outside of my knowledge set, so coming together and forming the practice started to make more and more sense.”

Snarkitecture was officially established in 2007, when Arsham moved back to New York City. (The firm derives its name from Lewis Carroll’s 1884 poem "The Hunting of the Snark,” which chronicles a band of eccentrics, aided by a blank map, as they pursue a creature that defies description.) Today, Snarkitecture is based in an inconspicuous brick building on an industrial block on the northern fringe of Brooklyn’s Greenpoint neighborhood.

Snarkitecture was officially established in 2007, when Arsham moved back to New York City. (The firm derives its name from Lewis Carroll’s 1884 poem "The Hunting of the Snark,” which chronicles a band of eccentrics, aided by a blank map, as they pursue a creature that defies description.) Today, Snarkitecture is based in an inconspicuous brick building on an industrial block on the northern fringe of Brooklyn’s Greenpoint neighborhood.

Inside, a number of Arsham and Mustonen’s furniture designs are arranged neatly around the surprisingly large space. An “excavated” mirror—which looks a bit like a topographic model of a land form topped by a perfectly flat lake—hangs on one wall. In the center of the space, a white conference table doubles as a regulation-size ping-pong table. In one corner, the prototype “ghost chair” looks like a standard chair covered by a sheet in a stiff wind. Arsham’s pet rabbit, Oliver, hops freely about (outlets and wiring have been raised just out of reach). The wall separating the two main spaces features life-size, Wile E. Coyote-esque cutouts of Mustonen and Arsham, the latter even including the signature fedora often perched atop Arsham’s head.

Currently, Arsham is preparing for an upcoming exhibition in Los Angeles, while Snarkitecture is designing the renovation of an old schoolhouse in upstate New York that will display a contemporary public art collection.

More conspicuously, the firm’s largest project to date will soon be carried out in south Florida. In 2012, baseball’s Florida Marlins will move into a new ballpark in Miami’s Little Havana neighborhood. Designed by Populous, the new ballpark —complete with a retractable roof—replaces the historic Orange Bowl, a Miami landmark that was once home to the University of Miami Hurricanes and the NFL’s Miami Dolphins. Arsham often went to the Orange Bowl as a child, and like many who visited the stadium or tuned in on television, his most distinct memory is of the iconic orange block letters above its entrance: MIAMI ORANGE BOWL.

So when Miami-Dade Art in Public Places put out a call for submissions for public artworks at the new ballpark, Arsham and Snarkitecture proposed a commemorative marker incorporating concrete re-creations of those letters. “When you think about a commemorative marker, you think about very obvious things,” says Arsham. “We wanted something that was a referent for people who knew the stadium—something that was recognizable. But for people who hadn’t been there, we wanted to make sure it wasn’t a dead object, that it would create a new experience.

“The letters are scattered around, some of them collapsed, some of them sinking into the ground. From some vantage points, they spell out new words; from other vantage points, they become abstract forms.”

Along with the commemorative marker, Snarkitecture also won the commission for a lighting installation that illuminates four columns supporting the roof when it retracts and covers a public plaza.Like a lighting intervention Arsham did previously for an I.M.Pei building in Miami, the column lights will slowly turn on and off continuously; at 180 to 200 ft. tall, they will create a lighthouse-like effect throughout the city. Because each light will operate independently, Arsham says it will suggest “four people standing in a room, breathing in and breathing out.”

Along with the commemorative marker, Snarkitecture also won the commission for a lighting installation that illuminates four columns supporting the roof when it retracts and covers a public plaza.Like a lighting intervention Arsham did previously for an I.M.Pei building in Miami, the column lights will slowly turn on and off continuously; at 180 to 200 ft. tall, they will create a lighthouse-like effect throughout the city. Because each light will operate independently, Arsham says it will suggest “four people standing in a room, breathing in and breathing out.”

In 2010, Arsham and Mustonen created a temporary retail installation under New York City’s High Line for the fashion designer Richard Chai. As with DIG, the project utilized large polystyrene blocks, which were hand-sculpted with hot wire cutters to produce shelves and alcoves to display clothing. “The tool defines the language of the form,” says Arsham. “When most people saw it, they asked which computer script we used to create the form. This is the direction that architecture is going in now—parametric design. But here, the entire project was cut by hand.”

“That’s intentional,” says Mustonen, noting that all of the material was returned to the manufacturer for recycling. “We are forcing ourselves back to the idea of making by hand.”

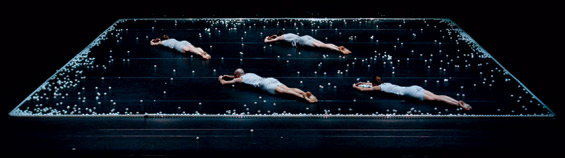

Performance view of Jonah Bokaer's "Why Patterns," (2010), with set design by Snarkitecture.

Earlier in 2010, the firm collaborated with choreographer Jonah Bokaer on “Why Patterns,” a performance piece commissioned by Dance Works Rotterdam.The performance, which premiered in Europe in February, involves four dancers and a simple set composed of just two elements: a frame of clear polycarbonate tubes and, at the outset, a single ping-pong ball. During the course of the performance, other balls are introduced—at one point, in a deluge of thousands from above—and manipulated by the dancers. “The choreographer presented us with the basic concept—a 1970s minimalist score by Morton Feldman,” says Arsham. “In line with that, our design is very simple. Like in a lot of the works where we’ve used a single material, we take that single material and find every possibility.”

“The process literally started with the first meeting, when Daniel brought a single ping-pong ball, which can be traced back to the ping-pong table in our studio,” says Mustonen, noting that “Why Patterns”will make its U.S. debut at the Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival in August. “We view it as a very reductive material that can be introduced on a large scale to create a lot of complexity.”