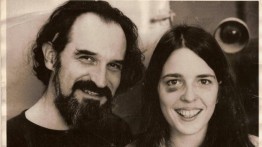

In Memory of Eugenie "Ersy" Schwartz

POSTED ON: January 6, 2016

Eugenie Schwartz, sculptor and long-time professor at The Cooper Union, passed away on December 30 in New Orleans, her hometown. A fixture of the art and architecture workshop for almost 20 years, Ms. Schwartz, who was known as Ersy, left an indelible mark on a generation of students who recall her as an extraordinary presence both for her technical virtuosity and her uncompromising, fearless personality.

“Ersy was a revelation,” said Kim Holleman, who graduated from the School of Art in 1995. “She was so completely hard-core, far out into her own identity.”

Her cast metal sculptures—precise, delicate and unnerving—frequently betrayed a sensibility both macabre and funny.

“If my works seems a little grim,” she told a New York Times reporter in 2011, “it is.”

Yet she made that work with exceptional brio. Famed for her loud laugh, unfiltered Camels, annual pig roast over the shop sand pit, and love of casting everything from shoes to mice, Ersy got palpable joy from teaching and making her art. “I remember Ersy being so happy when the building maintenance crew gave her another mouse,” said Dale Corvino, a 1988 graduate. “She cast it meticulously in bronze and gave it a parasol made from a broccoli floret.”

Ersy, whose work was exhibited in 2011 at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art in New Orleans, made small, detailed casts of objects from the natural world to the mythical. For “Homage to the Society of Ste. Anne,” she cast 105 bronze figures of imaginary beasts to represent a New Orleans parade in honor of the dead. Other works were momento mori for family and friends who had died. Ms. Holleman remembers Ersy calling her aside one day to show her a cast she’d been working on: a miniature bronze wheelchair set in a pyramid made of glass and brass surrounded by caplets filled with the ashes of her close friend Jimmy Vial. He had recently died of AIDS and the sculpture was Ersy’s tribute.

“It was so powerful. It scarred me but in the right way: it altered my psyche,” said Holleman. "Her sculpture was steeped in love."

Jen Collins, who graduated in 1993, remembers Ersy as “one of the most talented bronze casting artists in the world. She was able to immortalize everyday objects into exquisite pieces of art.” The fact that Ersy worked in scale models deeply affected Ms. Collins, who said that as fierce and direct as Ersy was, “she was also very kind and insightful. She really knew how to draw out her quiet and shy students like myself and the female students who might not feel comfortable articulating their ideas.”

A case in point was when Dawline-Jane Oni-Eseleh A’98 was a freshman. A steel sculpture she’d made had fallen on Ersy, who'd had to go to the hospital to get stitches. At the next class meeting, Ersy sought out Ms. Oni-Eseleh, who had been expecting a serious reprimand. “I can't remember her exact words, but I think it was a teary, ‘You gotta be careful.' That surprised me because I always thought she was so tough," said Ms. Oni-Eseleh. "The biggest take away for me at the time as a kid was that every one is a person with a life of her own.”

There seemed to be no casting challenge that Ersy wouldn’t take: as a young sculptor in New Orleans, clients asked her to cast an 18-foot alligator. Ersy didn’t hesitate, but it was an arduous job—months of wrapping the carcass in wet plaster, filling that mold with wax, creating channels for pouring in metal – all done in parts because the alligator was so large. One day after applying plaster, Ersy began to hear a high, shrill whistle that grew louder and more intense. She couldn’t find its source and began to panic when suddenly the entire carcass exploded: the organs of the gator had never been removed and the body’s gases had been increasingly compressed with each plaster application until it finally burst. “She made a gator bomb!” said Ms. Holleman. On that occasion, at least, Ersy avoided injury.

Ersy, whose work is represented by Arthur Roger Gallery, left The Cooper Union in 1999 when her mother was too ill to take care of herself. At that point, Ersy moved in to her grandmother’s house in the French Quarter, a home she wouldn’t abandon even during Hurricane Katrina. “The house is an illness with me,” she once said, but a few years back she moved into a garage she bought in the Bywater neighborhood of New Orleans, which she filled with her own work and that of her friends.

The New York Times reports that Ersy’s ashes, which will be carried in the Society of Ste. Anne parade during Mardi Gras this year, will be released into the Mississippi River. It seems a fitting tribute to an artist who, as Ms. Collins put it, “incorporated elements of nature into this really rigid material. It was like a breath, converting something rigid into something flowing.”