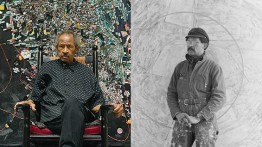

In Memoriam: Jack Whitten, Renowned Artist and Teacher

POSTED ON: February 7, 2018

Esteemed painter Jack Whitten, a 1964 Cooper graduate and painting professor from 1974-1995, died on January 20.

Perhaps best known for his deep explorations of materials, Whitten committed himself to art-making at a young age, and never looked back, despite considerable obstacles that included racism and poverty. But the incredible force of will that took him from segregated Alabama to the New York art world also imbued his canvases. Formally speaking, the paintings made during different periods of his life seem hardly related to each other. Yet, all of them are shot through with an urgency and intensity of color and line—whether he was making marks using brushes, poured-on paint, or tiles he created from layers of pigment.

Whitten’s journey to The Cooper Union was circuitous and painful. He’d always drawn and painted, but becoming a professional artist was inconceivable: he grew up poor in the city of Bessemer, Alabama, a place where the color line was so unyielding that black citizens were forbidden from even entering a museum or library. His father Mose was a miner who died when the artist was only eight years old. His mother’s work as a seamstress supported the family. Later she taught in a kindergarten that she’d founded. The young Whitten’s only exposure to art came from books and a painting done by his mother’s first husband, Monroe Cross, that she kept mounted on the family’s living room wall. Cross had been a sign painter—a highly unusual position for a black man at that time—and his tools, which his mother never got rid of, became Mr. Whitten’s first art supplies. He eventually took up sign painting as a teenager, earning money by painting price tags for local department stores. The money helped him support himself while a student at Tuskegee Institute, where he joined the ROTC to follow in an older brother’s footsteps.

It was there that he experienced what he termed a revelation. Rising from his seat in the midst of an ROTC class, he was moved by a thunder strike of clarity, asking out loud, What am I doing here? He left Tuskegee, where he had been studying biology, but beforehand was offered one bit of advice from an architecture professor there: apply to a school in New York called The Cooper Union. Though he enrolled at Southern University in Baton Rouge, he kept the professor’s advice in mind. At Southern he studied art and became involved with civil rights organizing, once meeting Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. after a talk the civil rights leader gave in Montgomery, Alabama. (Over the course of Whitten’s career, he painted many canvases dedicated to King.) But when he took part in a huge protest at the Louisiana state capital, Whitten was deeply enraged by the behavior of white onlookers: they threw feces and urine on the protesters. He immediately decided to leave Southern University. After throwing away all his clothes in the Mississippi River as a symbolic ablution—and a few days in New Orleans that led to a chance encounter with Fats Domino—he headed to New York, and by the fall of 1960 was enrolled at The Cooper Union.

Living with his burly, traffic cop uncle in Jamaica, Queens, Whitten quickly absorbed all that the school and the city could offer. He recalled the painter Robert Gwathmey, his drawing instructor, as helping him adjust to Cooper. He went to museums, studied the work of his classmates, and made a beeline to the famous hang out of the New York Abstract Expressionists, the Cedar Bar at 8th and University. There he met Willem de Kooning, who greatly influenced the early part of the young artist’s career. Robert Blackburn, whom Whitten recalled as the only black instructor at Cooper—he ran the school’s print shop—introduced him to Romare Bearden, who in turn introduced him to Jacob Lawrence and Norman Lewis. Armed with their recommendations and his outsized talent, he was awarded a John Hay Whitney Fellowship, a $4,500 prize that he used to buy a wealth of supplies.

Whitten, who described his early work as “abstract figurative expressionism,” once met John Coltrane as the painter was a regular habitué of jazz clubs around the city. The young artist tried to talk to Coltrane about art, but the jazz great wasn’t interested. Instead Coltrane talked about his experiments with composition. “He waved his hand and he used the word ‘wave,’" Whitten recalled. “He says, ‘Well, you know it's like a wave.’ This is what I remember the most… something went off in my head. It identified with what I was feeling in painting. It came directly out of his music, that way of playing that he had. Some people later called it training sheets of sound or a way of stretching out the notes, but I acquainted that with something that I was working with, which I call ‘sheets of light.’"

For many years, Whitten worked out of a studio on Lispenard Street in Tribeca, a place that Marina Gutierrez, Director of the Saturday Program, recalls as having a perfectly level floor. The artist built it that way so that he could better control paint as he poured gallons of it onto canvas laid on the ground. From there, he might work the paint using an afro pick or later a machine of his own devising, a sort of large squeegee with teeth, that he would pull across the canvas. “That was his way of replacing the hand,” Gutierrez said. She was referring to Whitten’s eventual rejection of the expressionism of Willem de Kooning.

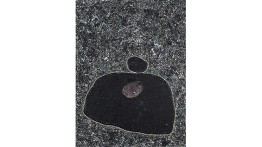

At one point, he began cutting into multiple layers of paint and using them as tiles. They were essential to some of his best-known paintings including the Black Monolith series—tributes to important black American figures like Ralph Ellison and Amiri Baraka—and "9-11-01" (2005), a 10 x 20-foot canvas memorializing the September 11 attacks, which he witnessed from his downtown studio.

“He laid complex mosaics inside a frame on top of a table,” said Richard Jacobs, who graduated from the School of Art in 1984. “He explained how he completed the painting by sliding a sharp tool component across the work in a few seconds, cutting all the mosaic pieces down to one level and filling the grooves with medium. That was the first time I began to be influenced by Jack’s concept of all over, all or nothing action which he perfected in so many of the techniques he invented, and was in many ways his legacy. Jack painted ‘Whittens’ decades before Gerhard Richter painted ‘Richters’.”

Beyond painting, his skills were wide and varied: he played tenor saxophone, was a master cabinetmaker, hunter, and construction worker; he had built store displays, manufactured olive oil, and spear fished. He spent his summers in Crete, Greece, with his wife, Mary Staikos, also a 1964 graduate of the school of art. There he carved wood, which functioned as both a break from painting and as he once said, “has been the single most important influence on my paintings’ plasticity.”

Though he would explore a particular technique in extraordinary depth, his work was constantly evolving. The influence of biology, politics, fractal geometry, surrealism can all be found in his oeuvre. It was the wide-ranging and fearless experimentation of Whitten’s work—in terms both of material and style—that so impressed his contemporaries and students.

He was a regular supporter of the Saturday Program, donating both money and time. Every year, he would host students at his studio, whether it was in Manhattan or in Jackson Heights where he kept his last studio. It was the highlight of the year. He would recount his youth, giving a searing first-hand account of living under segregation, and describe his art education, his thoughts on painting, and his belief that “you always get help along the way.” Jairo Sosa, a 2017 alumnus of the School of Art and the Saturday Program, remembers visiting the studio and seeing Mr. Whitten in his “uniform”—a lab coat and silver shoes and being impressed with the eclectic collection of materials at hand—shells, model planes, fish bones, light bulbs, and most memorably blood, all of which might end up mixed into his paint or attached to his canvases.

As a teacher, Mr. Whitten took a demanding but generous approach. Noting that listening was the critical element to good teaching, he expected students to deliver ideas worth listening to. “If I’m giving you something, but I also want you to give me something. If I’m in a situation and there’s no reciprocity, I get bored.” In a 2009 interview that he gave to the Smithsonian’s American Archives of Art he said, “I come from a point of view which says that no one teaches art and surely Jack Whitten doesn’t teach art…I teach the means to acquire art.”

He did just that for Tomashi Jackson, a 2010 graduate of the School of Art. Though she never studied with Mr. Whitten at Cooper, she did meet him informally at Yale. He agreed to come to her studio to look at her art. “We looked a lot and closely and talked a lot. One very significant thing that happened was that Jack saw what was happening around one of the works as a part of the language of the painting itself. I was rigidly considering that thing he saw as a practical necessity for the making of the thing. We kept looking and talking. The work matured that day.”

Though his art had been shown steadily throughout his career—at the Whitney, the Met, and the Studio Museum in Harlem— over the past decade, his work received greater recognition, including a retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego entitled “Jack Whitten: Five Decades of Painting.” This April “Odyssey: Jack Whitten Sculpture 1965-2017” will open at the Baltimore Museum of Art then travel to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In 2015, he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Arts by President Obama.

Richard Jacobs summed up Mr. Whitten’s greatest gift to his students: “He was engaged and engaging as a teacher talking about my work, but it was from his own passion for making art that I learned the most. Whitten lived in the abstract world, constantly creating personal ways to make art with integrity, individuality, and grit.”