A New Way to Read the Streets

POSTED ON: August 10, 2015

This past May a small group of just-graduated Cooper Union students and a faculty member met with officials from New York City's Department of Design and Construction, including its Deputy Commissioner Lee Llambelis and Commissioner Victor Caliese of the Mayor's Office of People with Disabilities (MOPD). They visited the MOPD to present a proposal, called Tactile City, that answered a request sent by the DDC on how to better enable the visually impaired to navigate construction zones. But in typical Cooper style, the group responded by giving an answer with a far more ambitious scope. Its development sprang from a collaboration that cut across all swaths of the Cooper community -- students, alumni, staff and faculty -- who brought their expertise from all three of the schools of The Cooper Union. If put into place, Tactile City would change the sidewalks of New York into pathways that can be read using a language of textures.

Teddy Kofman

Teddy Kofman

"It's a fascinating challenge," says Teddy Kofman AR'13, an instructor at The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture who was the faculty lead on the project. "As architects we don't only design a building. We also have a responsibility to create and form the spaces around it and their experience. These spaces and experiences must be accessible to everyone.”

The original DDC request was called, "Wayfinding for the Visually Impaired Around Construction Zones," and went out to art and design schools affiliated with NYCxDesign, an annual celebration. It came from the DDC office known as the Public Art and Design Initiatives that more typically coordinates public art works that are part of larger capital improvement projects. Xenia Diente A'99, works there. "This was our office's first outreach to design schools," she says. "It was a new experiment for us and it was very successful. A few schools responded but the most enthusiastic was Cooper Union.”

Teddy Kofman, who describes his own interests as focused on urban design, particularly the effect of grass-roots efforts on city spaces, took up the challenge. "I wanted this to be an inclusive project, engaging students from the school of architecture, art and engineering, because I saw the opportunities that each field could bring," he says. So, following a series of calls for participation to all current seniors back in April, he gathered a group of volunteers. Ratan Sur CE'15, a senior at the Albert Nerken School of Engineering at the time, was one. Charlie Blanchard AR'15, Chris Taleff AR'15, Sam Friedberg AR’ 15 and Thomas Heyer AR'16, all school of architecture students in their thesis and fourth years, also joined. From the School of Art the group recruited Emilie Gossiaux A'14, who is visually impaired, and Wai-Jee Ho A'11, who designed the project website and animation.

At the first meeting of the core group the project immediately expanded, Teddy Kofman says. "Construction work at times poses an interruption to pedestrian and vehicular circulation. For the most part it’s the longest temporary interruption. We see a range of elements that protrude onto public circulation across New York." Outdoor cafés, street fairs and open sidewalk bulkhead doors are examples. "We proposed a city-wide strategy to deal with everyday navigation. We proposed strategies that would allow people of all abilities to safely and comfortably navigate an interruption. With the visually impaired population in mind, our proposal operates primarily on a tactile level.”

Ratan Sur on "It Ain't Rocket Science"

Ratan Sur on "It Ain't Rocket Science"

The broad proposal presented to the DDC would gradually introduce a language of navigation built into the city's permanent sidewalks. Ratan Sur explains: "The idea is to use a rake to texturize concrete while it is curing and create a strip that goes down the center of the block. At each point of interest at the right or left of the block would be a textured pad embedded into the concrete while it was curing. Each pad denotes a point of interest." Entrances to a building would have texture different from a bus stop, for example. Changes in the texture could also signify direction and mark off quadrants, allowing for a form of way-finding or tactile address: e.g. third door, second quadrant heading north.

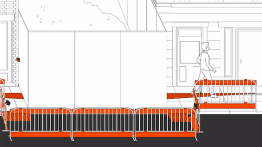

The Tactile City proposal addresses the original challenge of navigating interruptions with a strategy of adapting the permanent tactile language into temporary textured paths and handrails. A sound-emmitting device -- designed by Ratan to modulate its volume based on ambient noise -- placed at the entrance and at each corner of the detour would also indicate direction.

After the May meeting with the MOPD, the DDC has begun having internal discussions about ways to possibly implement a prototype at construction sites, according to Xenia Diente. Since then the Tactile City team has put its ideas into the world via its website, as well as out on the street at the annual NYCxDesign and New Museum's IDEAS CITY Festival. NY1, the Time Warner cable news channel, also did a feature on their work for the It Ain't Rocket Science series.

"It was very important for us to implement the findings of our research in a design proposal, thereby making it accessible,” Teddy Kofman says. "We want to support the city in their effort to help people of all communities. We would be happy to continue to work with the city on a prototype if there’s an interest." At the very least the team is hoping for the proposal to be incorporated into the next edition of the Active Design Guidelines, a handbook published by the DDC describing strategies for creating healthier buildings, streets and urban spaces.

Besides requiring the expertise in urban planning, aesthetically thoughtful design and civil engineering fostered at The Cooper Union, the Tactile City proposal is pure Cooper Union in another way, according to Teddy Kofman. "The methodology by which we approached the problem is in my view one that is continually fostered within this institution. We were given a problem and we looked at it and said, 'Well that's not quite the problem. We'll reframe it. We understand what we’ve been asked to do but we choose to look at it within a much larger picture.' It's challenging what you are told, not avoiding it.”