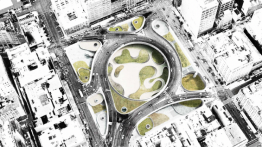

Ballman Khapalova Propose Ambitious Park Plan for Lower Manhattan Site

POSTED ON: April 7, 2022

Last winter, the writer Karrie Jacobs took to the AIA’s publication, Oculus, to urge designers to look to urban infrastructure as the basis for new civic spaces. Specifically, the country’s many roadways, Jacobs argued, were built on a grand scale that could now be reimagined for more communal purposes. “The highways that carved up our densely developed urban neighborhoods were once the height of progress, the apex of mid-20th-century notions about personal transportation. But the rights-of-way created for those same highways could become the symbols of a 21st-century renaissance, one in which we repurpose what we’ve got to get what we need.”

Long before Jacobs published her piece, Peter Ballman and Dasha Khapalova, graduates of The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture, had developed just such a plan, a proposal to transform a two-block site in downtown Manhattan—one built for cars—into a public space that will reunite sections of the neighborhood long separated by the roadway. As the pair—the principals of the firm Ballman Khapalova—have put it, “An obstacle will be turned into a place of connectivity.”

Called Rotary Park, their proposal calls for green space, indoor meeting and performance areas, and playgrounds, on a 4.5-acre site where the Holland Tunnel’s circular exit roadway is located. The team isn’t suggesting the roadway be demolished; rather, they are proposing to lift the road and reclaim the land underneath it. The design has already garnered many awards including the 2019 Architect's Newspaper Best of Design Award for Unbuilt Urban Design, the 2021 AIANY Design Merit Award for Urban Design and recognition as a 2021 Architizer A+ Awards Finalist in the Unbuilt Transportation category. The project builds on the premise that infrastructure, which usually occupies a sizable footprint, can also serve as a public space for multiple purposes. Although still a proposal, the pair have assembled a formidable team to bring the project to life including the structural engineering firm Thornton Tomasetti, climate engineers Transsolar, Sciame Construction, and other firms with specialties in landscape architecture, precast concrete, and even naval engineering. Together with community stakeholders, the architects have dedicated the last three years to meeting with community boards, the Port Authority, and residents to promote a plan that is driven by community needs as well as the site’s history.

The site, which is currently known as St. John’s Park, is owned by the Port Authority, and is part of a fascinating chapter in New York history. Originally a marsh, the area was a contested border between the Lenape and Dutch settlers. The Dutch gave the acreage, which they’d converted into (not terribly good) farmland, to formerly enslaved people who were granted a status referred to as half-free. Some historians believe that when the British took possession of the area, land rights were revoked, and many Black residents moved north, resettling in an area that was called Little Africa, which is the present-day West Village.

Later, the site was purchased by Trinity Church as a speculative real estate deal: the church erected a chapel and exclusive homes all arranged around the park, which was gated, much like today’s Gramercy Park. And in a still later incarnation, the site was used as a train depot. The architects are interested in learning histories of the site, they said, because of their training with the late Professor Diane Lewis’s renowned fourth-year studio. “The whole concept of city as psyche…packed full of all of these kinds of latent motivations,” Ballman added.

Khapalova, who last month was named one of Architizer’s 100 Women to Watch in Architecture, pointed out that for much of its history, the land was in private hands: “It was always exclusive to one group who kept another group out. So for us, what's very important is that this would be the first time that the site would be open to everybody. It would be open not just to the neighborhood, but the whole city.” At the same time, she said, the site’s history would help drive the project’s design and programming.

To start with, much of the site will be dedicated to open green space and, most critically, will connect parts of the neighborhood that are now only accessible to each other via an overhead walkway or by walking well out of the way to circumnavigate the area. Residents and visitors alike will be drawn not only to gardens, outdoor art, and playgrounds, but to Rotary Park’s multi-purpose interior spaces where a whole host of events can be programmed: film festivals, concerts, fitness classes, civic meetings, and art exhibitions.

Khapalova explained that precast concrete walls will be erected around the roadway itself to essentially insulate Rotary Park from traffic noises and to ensure that fumes are directed upward. “The concrete can be treated in such a way that it doesn't just reflect sound, but it actually dampens it.” The pair stressed that the Holland Tunnel will not need to be closed at all during construction. Only one offramp at a time will be closed so that the overall roadway will remain active.

But they don’t want only to mitigate the air and noise pollution caused by the roadway; they have designed Rotary Park to act as a piece of sustainable infrastructure that will act as a catchment to get stormwater off the streets of the surrounding area. Many of the community stakeholders have particular interest in the multiple ways that the park and its re-imagined roadway can notably improve the site’s environmental impact.

Ballman sees the project not only as a way to add much needed public open space to New York, but also as a mandate for the role of the architect. “Typically, by the time a project has reached an architect, its scope has already been determined by the city. There’s a lot of policy that has already been sorted and developed, and many other agents and stakeholders who have significantly defined the scope of work.” Instead, he and Khapalova want architects to be essential partners from the start of a project, driving critical inquiry about a site, its relationship to its neighborhood and the city at large.

To learn more about Rotary Park and the efforts to make the proposal a reality, visit the team’s website.